Stoicism is not just self-help for men

No, Stoicism is not just self-help for men, but it isn't hardcore cynicism either.

On December 5th of this year, Laura Kennedy posted a substack article called “Is Stoicism Just Self-Help for Men Now?”

It argues that those that practice modern Stoicism often deviate from 3 core philosophical commitments held by the ancient Stoics. And that by changing these parts of Stoicism, Modern Stoicism has not just modified or updated ancient Stoicism, destroyed its coherence as a philosophical or ethical system. In her words:

“...the result is incoherence — modern stoicism is attempting to achieve something that ancient stoicism was designed to resist.”

According to Laura, the three commitments that are held by the ancient Stoics but broken by modern practitioners are:

1. Stoicism requires theism.

2. Stoicism and ambition are incompatible

3. Stoicism is a philosophy of individual non-conformity.

To cut to the chase, I think Laura has gone too far here, and is mistaken about 2 and 3 in particular.

But her article also got me thinking about something I’ve been chewing on for a while. Why should we care what other people do or practice at all, if it makes them happy or improves their lives? Should we even care if someone who isn’t a Stoic calls themselves one?

In other words, I want to address a two questions:

First, what is the value, if any, of gatekeeping Stoic philosophy?

Second, where does Laura’s specific gatekeeping / definition of Stoicism go wrong?

Part 1: What is at stake with gatekeeping Stoicism: Why we should care about these kinds of discussions.

When I refer to stoic gatekeeping, I mean conversations about what, or who, even qualifies as Stoic. Gatekeeping is a kind of definitional exercise.

These questions can be about who is Stoic: Was Cicero a Stoic? What about Socrates or Marcus Aurelius? Ryan Holiday calls himself a Stoic, but is that really true?

Or they can be what beliefs or practices are Stoic: Can you be a Stoic and a Buddhist? Can Stoics be atheists? Are cold showers Stoic? Can a Stoic want to be rich and successful?

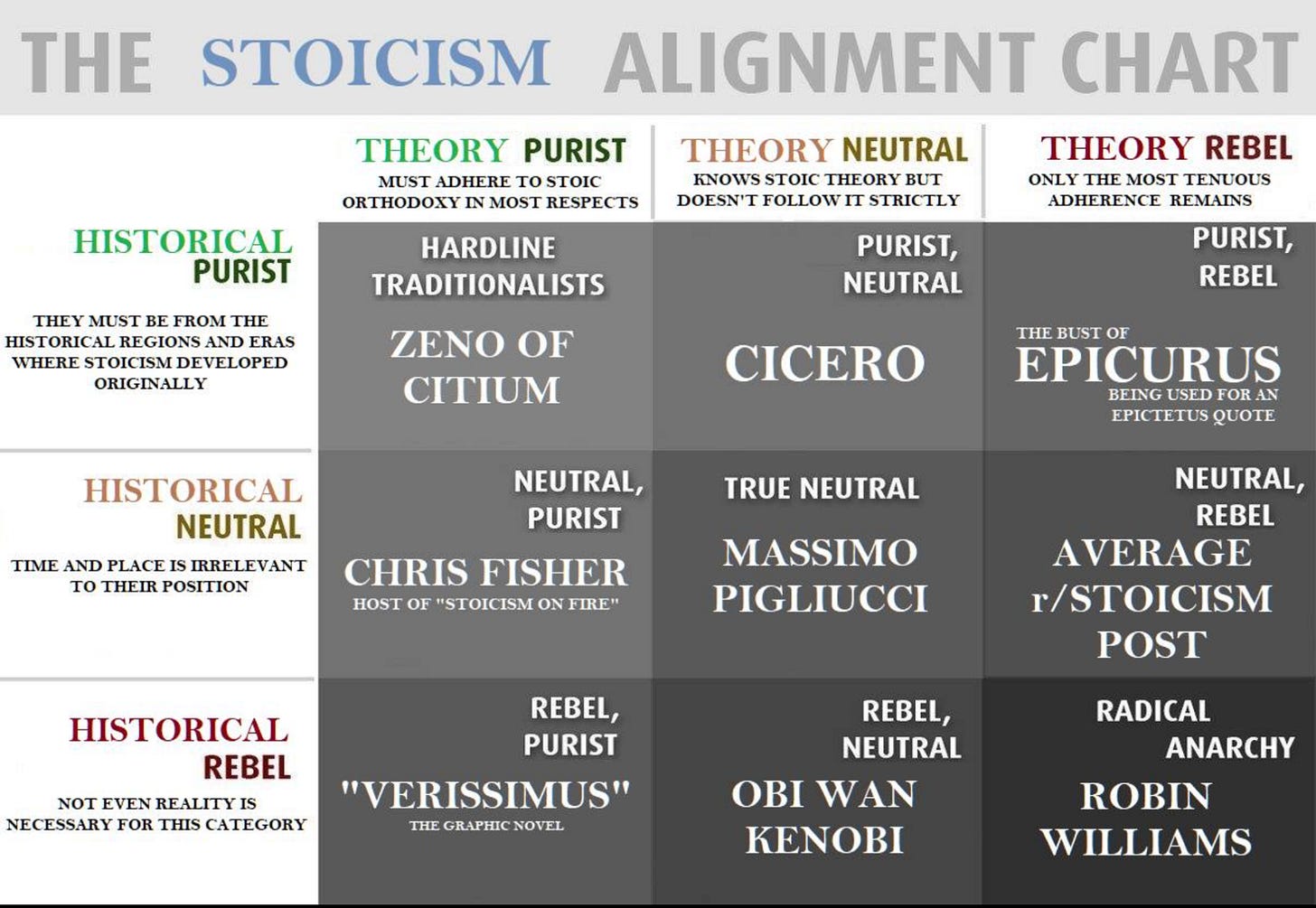

For example - the Stoicism alignment chart below (not my own) shows some ways you might think about defining who does or doesn’t count as a Stoic. Cicero is from the right time, but his beliefs are a bit off. Chris Fisher - host of the “Stoicism on Fire” Podcast is a theory purist, but he was born 2000 years after Marcus Aurelius. The more to the top left you are - the more hardcore your definition. The more to the bottom right, the more lenient and inclusive.

Laura’s article focuses on defining Stoic theory, with implications for the people that can call themselves Stoic. Her claim is that these 3 commitments are core Stoic beliefs, so if you disagree with them you are not Stoic - no matter what you tell yourself. Using the chart above - she’s a theory purist and historically neutral. You can be a Stoic today, but you better believe what the ancient Stoics believed if you are going to call yourself that.

Laura is of course not the only person to write on this topic. Go on any Stoic facebook group, discord, or reddit thread and you will see these kinds of conversations constantly. There is a particularly heated debate around the necessity of a Stoic god for Stoic ethics. This is sometimes portrayed as one of the main differences between the Traditional Stoic movement and the ‘Modern Stoic’ movement, with Modern Stoics being more liberal about the possibility of an agnostic or atheist Stoic way of life.

The Benefits of Gatekeeping Stoicism:

Gatekeeping can be very useful. There is a reason we are interested in defining Stoicism, and putting other people in boxes. Gatekeeping has 3 main benefits in my view.

It maintains high standards in the pursuit of truth.

I have a PhD in philosophy, where I specialized in Stoicism. The function of a PhD examination, within the academy, is basically institutional gatekeeping. You do not automatically pass just by completing the work, you must have made an original contribution to research as assessed by a team of your peers. You assemble a committee to review your work. You bring in an ‘external examiner’ (mine was Brad Inwood) who is an acknowledged expert on the topic and works at a different university. Their function is in part to provide an unbiased opinion - to ensure the standards for passing are objective and no poor candidates are pushed through.

I think this is a good thing. A PhD carries a certain degree of status because it signals excellence in research. And the guarantee of that excellence is gatekeeping. Some people fail - they don’t get to be a part of the club.

Whether you are practicing Stoicism or just interested in philosophy, it is good to have people that maintain high standards.

It is helpful for someone to tell you that your interpretations of Stoicism aren’t good enough - they are not coherent, they contradict this other passage or book you haven’t even read yet. It is helpful for people to call out that you might be leading yourself down a dead end, or that what you are describing as your personal philosophy sounds more like Epicureanism or Buddhism than Stoicism.

Philosophical gatekeeping properly applied has a truth-preserving function. And Stoicism is very much about the truth of things.

It forces us to think very deeply about what the essential qualities of Stoicism are.

Defining Stoicism means picking out its essential qualities. Which pieces, if removed, mean it is no longer Stoicism?

This is a complicated question, because not all Stoics actually agreed on everything. Seneca does not talk about emotions the same way Epictetus does for example. However, there were many lines all Stoics were not willing to cross though, a series of key commitments. Defining those precisely is actually a very helpful philosophical exercise. And if defined properly - they should be enforced. Because if they are not, then there is a risk people will get confused, or think Stoicism contradicts itself.

I am very sympathetic towards Laura’s pursuit of philosophical coherence, and certainly the Stoics would have been too. She makes it clear in her piece, she has no objection to people adopting parts of the Stoic system they find helpful - just don’t call yourself a Stoic.

I actually think Laura’s first commitment - that Stoicism is Theistic - is a good example of an essential part of ancient Stoicism. The Stoics believed in a stoic god, although one very different from many other religions. God is the divine, ordering, rational principle of the Universe. However, many modern readers choose not to accept this, ignore evidence, or say it was not an essential part of their system (even though it is for the ancient Stoics).

I suspect people sometimes misunderstand Stoicism because they are not actually trying to define Stoicism. They are trying to define their personal life philosophy and in the process shove it into the ‘label’ of Stoicism.

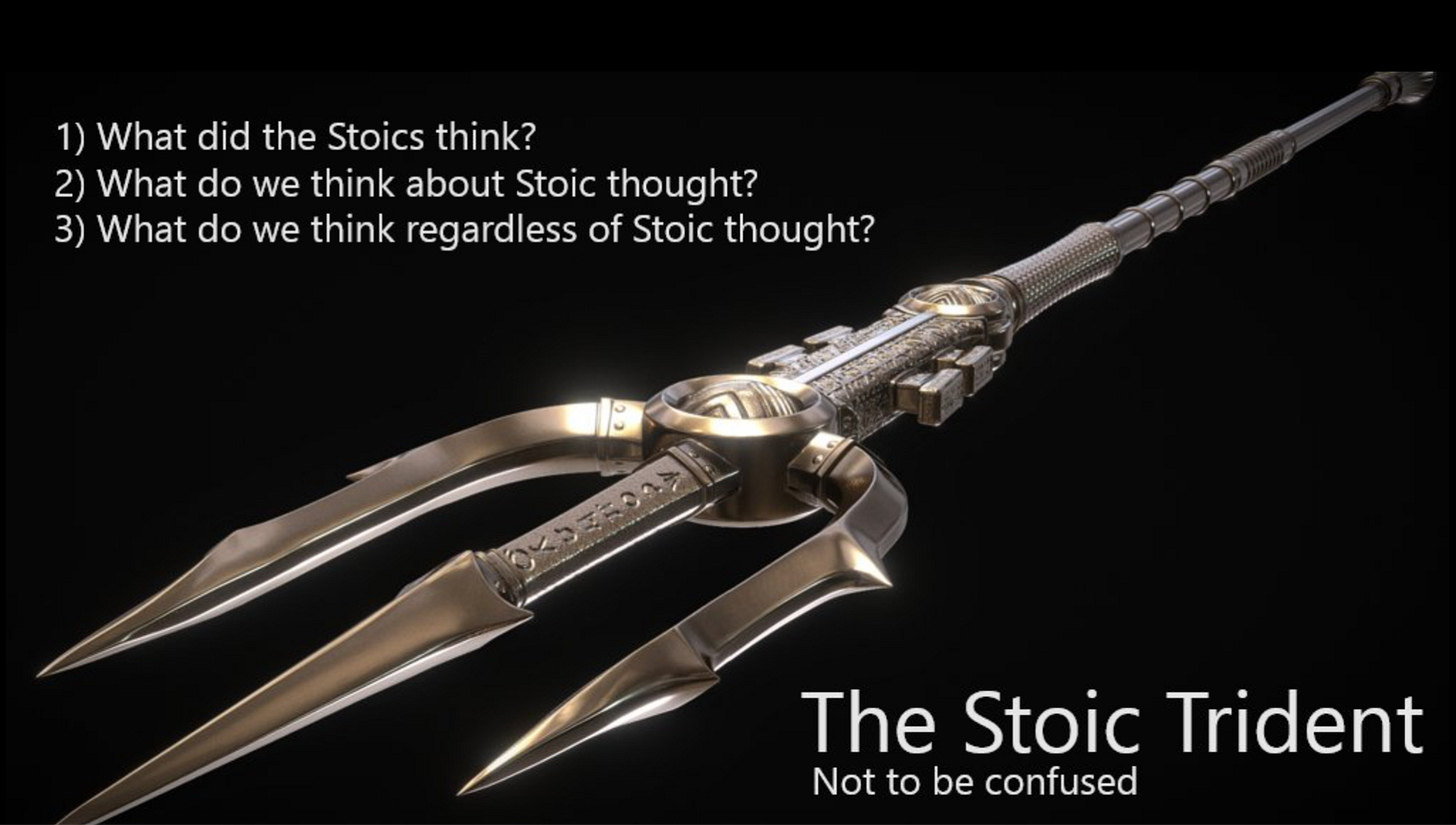

James Daltry of Living Stoicism proposed what he calls the ‘Stoic Trident’. The trident states that there are 3 questions, often conflated, that must be kept separate.

When we are defining/gatekeeping Stoicism, we are discussing the first question only: What did the Stoics think? This question needs to be answered properly before we can move on to questions in categories two and three: Do we agree with the Stoics? Do we think Stoic arguments are convincing? Are some Stoic arguments weaker than others? Do some Stoic ideas need updating in light of modern physics and psychology?

But to answer questions in these categories accurately, we first need a foundation which we all agree on to ensure productive conversation and shared understanding.

In years of teaching Stoicism, I’ve seen hundreds of people try to map their own intuitions onto Stoicism. It is counter productive if your goal is to understand Stoicism, and gatekeepers play a useful role in policing this and correcting those who have made honest mistakes.

As practitioners, it can have a motivating effect.

Third, if you think Stoicism is a craft meant to be practiced, then you want to be held to appropriate standards. I don’t want to be called a Stoic unless I am one. And if I fail to live up to that standard, I want that gap pointed out to me.

Epictetus used to mock his students. He would ask them to show him a single Stoic.

Observe your own behaviour in this way, and you will find out what school you belong to. You will find that most of you are Epicureans, and some few are Peripatetics, but pretty feeble ones at that. For, by what action do you prove that you think virtue equal, and even superior, to all other things? Show me a Stoic if you have one. Where, or how? You can show, indeed, a thousand who can repeat the Stoic quibbles. But do they repeat the Epicurean ones less well? (Epictetus, Disc. 2.19.19-22; Trans. Hard)

This is gatekeeping at its best. You claim to be Stoics, Epictetus says, but when I look at you I see Epicureans and Aristotelians. That is honest feedback.

Epictetus even goes further - he has a tendency to be dramatic:

Show me someone who is sick, and yet happy; in danger, and yet happy; dying, and yet happy; exiled, and yet happy; disgraced, and yet happy. Show him to me, for, by the gods, I long to see a Stoic. But you will say, you have not one perfectly formed. Show me, then, one who is in the process of formation, one who has set out in that direction. Do me this favour. Do not refuse an old man a sight which he has never yet seen. (Epictetus, Disc. 2.19.24-25; Trans. Hard)

I want to note that I don’t actually think Epictetus is being serious here. I don’t think Epictetus would claim to have never seen a Stoic, a sage maybe, but not a Stoic. It’s a motivating device and a useful one. High standards push us to improve.

The Risks of Gatekeeping Stoicism

However, as I see it there are 2 main risks to focusing too much on gatekeeping what is or isn’t Stoicism:

It can make people pedantic and too theoretical

Stoicism is about achieving knowledge but knowledge is best demonstrated through action - not through academic debate.

Epictetus describes a philosophical education as a two part process. First you learn the theory, then you have the difficult task of putting it into practice: As Epictetus says:

The philosophers, therefore, first exercise us in theory, which is the easier task, and then lead us to the more difficult: for in theory there is nothing to oppose our following what we are taught; but in life there are many things to distract us. (Epictetus, Discourses, 1.26.3. Trans. Hard)

Putting ideas into practice is harder than definition. Being the best at describing the Stoic virtue of justice is easier than being a kind friend. Someone who is courageous in the face of evil is to me more Stoic than someone who has published on Stoic ethics.

Understanding Stoic theory is a means to an end, but the end is to live like a Stoic, not to win debates.

It can actually get us further from the truth

Another problem with gatekeeping is that, if you get it wrong or do it poorly, you distort the truth not preserve it.

Gatekeeping involves defining what does or does not qualify as Stoicism.

But Stoicism has changed and evolved. Chrysippus refined Zeno’s work. Epictetus pushed his students to apply Chrysippus’ work to their own life in novel ways.

Yes, we need to define what Stoicism means, but if that identity is too narrow, we are likely making a mistake. To use a religious example, we need a definition of a christian to have meaningful conversations, but if your definition is so specific it ends up with only 1000 people qualifying, you’ve likely made a mistake. And now your definition is impeding meaningful conversation, not helping it.

It reminds me of an old joke:

“Once I saw this guy on a bridge about to jump. I said, “Don’t do it!” He said, “Nobody loves me.” I said, “God loves you. Do you believe in God?” He said, “Yes.” I said, “Are you a Christian or a Jew?” He said, “A Christian.” I said, “Me, too! Protestant or Catholic?” He said, “Protestant.” I said, “Me, too! What franchise?” He said, “Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Baptist or Southern Baptist?” He said, “Northern Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist or Northern Liberal Baptist?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region, or Northern Conservative Baptist Eastern Region?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region.” I said, “Die, heretic!” And I pushed him over.”

We should be holding modern Stoic practitioners to a high-standard, not trying to find the heretic.

Final Thoughts: Good gatekeeping finding a balance between logical sloppiness and being too theoretical or narrow.

So then we seem stuck between a rock and a hard place with gatekeeping. Too much gatekeeping, and we are exclusionary pedants missing the forest for the trees. Too little gatekeeping and we lose the philosophical coherence of Stoic philosophy and its value along with it.

So what’s the answer? Well, like any other craft - it depends.

My view is that the standards of helpful gatekeeping depend on the project at hand. For academic philosophy, we should be clinical and precise. If the sole exercise is to define Stoicism, then we should be as in the details and theoretical as possible.

But if the project is self-improvement and practicing Stoicism, then gatekeeping should be done carefully. We want to define Stoicism because it is helpful for our practice, but we don’t want to confuse the means with the ends. We can’t define our way into being better people.

Part 2: Stoicism is not just self-help for men, but it isn’t hardcore Cynicism either.

So with that in mind I want to turn to Laura’s partial definition. Does she succeed in her gatekeeping exercise? As a reminder, she posits that there are three commitments held by the ancient Stoics but broken by modern practitioners:

1. Stoicism requires theism.

2. Stoicism and ambition are incompatible

3. Stoicism is a philosophy of individual non-conformity.

First, I want to clarify that I think Laura is gatekeeping for the right reasons. As she says:

“Well look. This column isn’t my attempt to police who is permitted to find stoicism helpful. Tattoo amor fati on your neck! Hang a memento mori in your office! Wear a toga when nobody is looking! Seneca won’t come back and belt you over the back of the head with his dusty sandal. My concern is philosophical coherence — whether the modern version so many of us value, which borrows its credibility and worldview from the ancient system, still counts as stoicism in the philosophical sense.”

Her interest is not in excluding people from improving their lives - it is in philosophical coherence.

Also, she is not trying to enforce an unrealistic standard no one can meet. She is theory purist, but historically neutral. Her view is that it is possible for people to be Stoics today, but we can’t borrow an ancient school’s credibility and name if our own beliefs are incoherent with that system.

That is a sound approach. However, I think she is wrong about Stoicism. I think she is a theory purist who gets the theory wrong.

So let’s go through these in order.

Stoicism requires theism

The argument:

Stoic ethics is about aligning your actions, beliefs, and motivation with nature / the universe. This is what we call virtue.

It is valuable to align yourself with the universe because the universe is providential, deterministic, and divine - it is identified with god.

We can ground virtue in something else, but then we are no longer doing Stoicism.

I agree with Laura, or at least I think the ancient Stoics would agree with Laura.

There is an interesting debate to be had as to if you could secularize Stoic ethics - if you could retain a modified Stoic teleology and claim virtue is the only good if the Stoic god did not exist. In other words, you could argue that ancient Stoicism posits that there is a kind of god, but it doesn’t require one to still be Stoicism.

However, I am not sure I am convinced that this move works. It would be an ethical system very similar to Stoicism - but the Stoics are explicitly theistic.

Stoicism and ambition are incompatible

In the classical stoic system, ambition does exist, but not as we mean the word. The stoic version is orexis or striving. It refers to acting energetically in the world in line with virtue but without personal investment in outcomes. Stoics can coherently foster ambition in this way — they can act vigorously in the world. What they can’t do is assign value, meaning or motivation to the results of their actions, and they cannot derive identity from these outcomes either. (Source: Laura Kennedy)

The argument:

The outcomes of our pursuits are externals (indifferents)

Stoics cannot assign value, meaning or motivation to the results of their actions, and they cannot derive identity from these outcomes either.

Stoics cannot do anything instrumentally - for the purpose of achieving an external outcome.

If you are doing something for preferable outcomes (indifferents) - you are not doing Stoicism.

I’ve done my best to charitably summarize Laura’s view above. According to her, the Stoics think that anything external is indifferent and that we can’t care about externals.

So any sort of ambition (setting instrumental plans to achieve an external outcome) is anti-thetical to Stoicism.

You can take an influential role in society as a stoic, but you cannot treat that success as meaningful or use stoicism in order to secure or advance within that role. You can govern, but not for outcomes like making constituents happy or to improve an unjust system (there are no unjust systems, only individuals acting without virtue). You can lead, but not to create a legacy. You can contribute to the public marketplace of ideas, but not to elevate your status. No matter what you are doing, you must do it virtuously, and never instrumentally. (Source: Laura Kennedy)

But this is not what the orthodox Stoics think. Actually, this was closer to Aristo’s position. Aristo was a contemporary of Zeno, the founder of Stoicism. He argued that the only thing that could be ascribed any value was virtue, therefore it did not make sense to call some ‘indifferent’ things like health and wealth preferred, and others like death or pain dispreferred.

The only thing of value to Aristo was virtue and vice. So the value of external things like pain, pleasure, wealth or fame only ever depended on the exact moment you were selecting them and whether that selection was virtuous in the moment.

But the Stoics, even the orthodox early Stoics, are explicitly against this position. They have two sets of values. Good and Bad which correspond to virtue and vice, and then preferred or dispreferred things, which correspond to those things that tend to be worth selecting according to our physical and social nature as humans.

This allows a lot of common sense outcomes. It is fine to prefer money, unless there is a reason seeking wealth in this instance is viscous or unethical. I can build a successful business that helps people, but I can’t steal or exploit my workers because I care more about money than treating others well.

Ambition, defined as the pursuit of external things as goods, is impossible. But ambition in terms of desiring a successful life is the point of Stoicism. We want to be happy good people, we desire that outcome. And part of that outcome means doing what is in our power to achieve certain external goals.

The pursuit of those external goals just needs to be balanced with virtue or good character, and a willingness to accept failure if we don’t achieve our plans.

Consider Epictetus on the Reserve Clause exercise:

“When you are about to undertake some action, remind yourself what sort of action it is. If you are going out for a bath, put before your mind what commonly happens at the baths: some people splashing you, some people jostling, others being abusive, and others stealing. So you will undertake this action more securely if you say to yourself, ‘I want to have a bath and also to keep my choice in harmony with nature.’ And do likewise in everything you undertake. So, if anything gets in your way when you are having your bath, you will be ready to say, “I wanted not only to have a bath but also to keep my choice in harmony with nature; and I shall not keep it so if I get angry at what happens.” (Epictetus, Handbook, 4)

It is ok to want to have a bath, because baths are nice and maybe you’ll see some friends. These things are fine to want! The Stoic just also always remembers the more important goal - that they can only want these things if they don’t fall out of harmony with nature in trying to get them.

Laura’s obviously right that you can bastardize Stoicism for your own un-Stoic ambitions. I think about the example of the Stoic serial killer, adopting certain parts of the dichotomy of control to efficiently hunt down victims and avoid capture.

But the real Stoic has ambitions - to be a good parent, a good neighbour, a good friend, excellent at their career. And this is not anti-thetical to Stoicism, unless you have to choose between these ambitions and your character. Then the Stoic always chooses their character.

Stoicism is a philosophy of individual non-conformity

If stoicism is incompatible with modern ambition because it strips outcomes of moral meaning, it is incompatible with modern political and collective life because it similarly strips groups, systems and structures of moral meaning also. Hopefully by now it’s clear enough that stoicism is a philosophy of radical internalism. (Source: Laura Kennedy)

The argument:

Social norms have no intrinsic moral authority for the Stoics, so the Stoic cannot act for collective aims

Systems cannot have moral properties, so the Stoic cannot identify or target ‘unjust’ laws or ‘broken’ systems.

Because Stoics cannot act ambitiously or with instrumental ends, Stoic politicians cannot invest in specific outcomes (e.g., less child homelessness)

Laura’s argument here has many components, but as I understand it, her main point is that Stoics cannot engage effectively with politics or collective action, because they cannot claim value judgements about political systems, and they cannot have political goals that are outcomes based.

I think there is a fundamental misunderstanding of Stoic ethics here.

First, the argument that Stoicism is individualistic is actually contradictory to the claim about Stoic theism made above. Stoics are not individualistic because we are all connected as part of the same divine universe. So this argument has serious problems, even in light of what Laura has already argued for.

Second, Stoics have language for talking about injustice. It is not an individualistic philosophy entirely unable to have basic conversations around how people should organize and treat each other. Afterall, Zeno, the founder of Stoicism, wrote a book called the ‘Republic’ which outlined the ideal state in line with Stoicism. Will Johncock has recently written an entire book on why Stoicism is about focusing on the community and helping others.

In Laura’s piece, there is no mention of the 4 Stoic virtues, one of which is Justice.

Justice includes the subvirtues of kindness, good fellowship, and fair dealing (as well as piety). So the Stoic is easily able to point to something as an example of cruelty instead of kindness, unfair treatment instead of fair dealing.

The Stoic politician is able to, in striving to act out virtue, attempt to end an example of how society is failing to live up to good fellowship (such as having an abundance of homeless children).

Seneca on On Clemency says:

“But no school of philosophy is more gentle and benignant, none is more full of love towards man or more anxious to promote the happiness of all, seeing that its maxims are, to be of service and assistance to others, and to consult the interests of each and all, not of itself alone.” (Seneca, On Clemency, 3.3, Trans. Stewart)

Just like Laura was channelling Aristo before - here she seems to be channeling the cynics. The cynics were a contemporary school of ancient philosophy but much more extreme than the Stoics.

According to Epictetus, the Stoics think humans have social roles that give us moral responsibilities. We are siblings, children, parents, politicians, coworkers - and each of these roles come with certain requirements.

But the cynics only have one role - to act out virtue. For this reason, they give up their other roles. They ignore social norms and family ties. Diogenes famously slept in a barrel. He urinated in public. He pushed the limits of his body, and never ate extravagantly.

Epictetus describes Diogenes as a scout gathering information for our benefit. He acted out a radically anti-social and individualist life to demonstrate the resilience of people and our capacity to flourish even while living against social norms.

But Epictetus is clear, we are not all made to be Diogenes. This is a special calling for a special few. Yes, Diogenes would make a terrible politician, and would not try to end child homelessness, but he was not meant to be a politician.

And even Diogenes, Epictetus says, loved other people:

“What! did Diogenes love nobody? [He] who was so gentle and benevolent that he cheerfully underwent so many pains and miseries of body for the common good of mankind? Yes, he did love them; but how? As became a servant of Zeus; at once taking care of men and submitting himself to god. That is why the whole earth, not any particular place, was his country. ” (Epictetus, Discourses, 3.24.64-66. Trans. Hard)

There is a reason Stoicism is more popular than cynicism. It is less extreme, more balanced, more grounded in common sense. Stoics can become politicians who strive to help the world. Stoics just can’t become one who sells out their values for power or wealth.

Conclusion

There is a risk in losing the philosophical coherence, rigor, and value of Stoicism if we are too lenient with what it means to be a Stoic. We don’t want to expand that circle too broad, and we have seen that with the pushback against Broicism and $toicism.

But we can also make the mistake of making the standard too high, and the circle too small. In terms of how we practice, it can happen by gatekeeping beginners trying to learn about Stoicism for the first time. In terms of theory, this can happen by pushing Stoicism to its theoretical extreme.

But the theoretical extreme of Stoicism already existed in Diogenes and Socrates. And Diogenes of Sinope and Socrates were not the only Stoics of ancient times. Likewise you do not have to live in a barrel and forsake politics or an ambition to call yourself a modern Stoic.

The Stoics were not cynics. Caleb and I often refer to Stoicism as ‘cynic-lite’ for this exact reason. The cynic school was extreme. The Stoics were more grounded in common sense, more open to ambition and collaboration.

Stoics should have long term ambition and want to work with others to change the world for the better. And arguing otherwise is not holding modern Stoics to a high standard; it takes us farther from the truth.

A great response to Kennedy's piece.

Nice work, Michael - I also thought that Kennedy had some key things wrong, and you've carefully shown what they were.